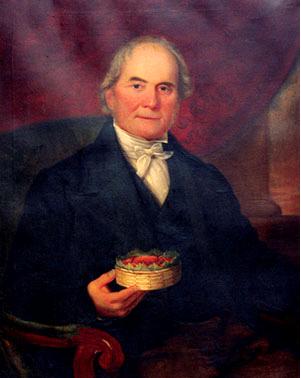

Joseph Myatt (1771-1855)

Market gardener and pioneer of rhubarb and strawberry growing in England.

____

by Kathryn Darley

____

by Kathryn Darley

JOSEPH MYATT’S BIRTH IN STAFFORDSHIRE

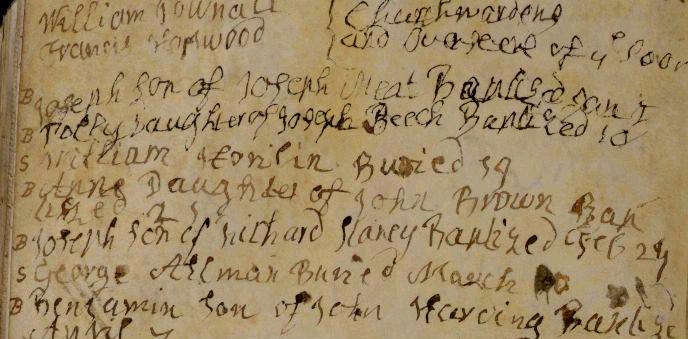

Joseph Myatt was born in late 1771 in Maer, a village south-west of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, England. There is a ‘Joseph Meat’ in the baptismal registers of St Peter’s Church at Maer, for January 1, 1772. As an elderly man, Joseph himself gave ‘Maer’ as his birthplace and ‘seventy-nine’ as his age when he was registered in the 1851 census, Therefore the baptism record at Maer is likely to be him with the name spelled phonetically.

Baptism register from St Peter’s at Maer. Near the top of this section we can make out “Joseph son of Joseph Meat Baptised Jan 1”

FAMILY AND CHILDHOOD

As shown on the baptism register, Joseph Myatt’s father was also called Joseph. This (father) Joseph Myatt was baptised in Maer in 1746. Joseph's mother Ann Bailey was about ten years younger than her husband; she was baptised at Maer in 1756. Joseph and Ann married in 1769. Ann may have been born a year or two before her baptism, but she was still probably only fifteen or sixteen when she married and her oldest son Joseph was born. This young age for starting a family was not unusual for that period. Other children baptised in St Peter’s at Maer who had a father named Joseph Myatt are William (born in 1772), Benjamin (1776), Elizabeth (1779), John (1781), Mary (1785), James (1786), Catherine (1789) and Margaret (1793). It is probable that these were Joseph Myatt’s siblings; John Myatt, for one, did have a connection with Joseph later in life.

Nothing is currently known of Joseph Myatt’s early life in Staffordshire but it can be assumed that he was raised in that rural village setting since so many younger siblings were born there. Joseph could read and write and later conduct business so he must have received an education – by no means guaranteed in those days. We can assume that Joseph started working as a gardener near Maer.

Joseph Myatt later worked on the gardens of large country estates before starting his own market gardening enterprise, so we can speculate that his early work involved the production of fruit and vegetables as well as aesthetic gardening. Unfortunately there are no records of his work prior to the age of thirty.

PRESTWOLD HALL, LEICESTERSHIRE

By 1802 when he was thirty years old Joseph Myatt was living in Leicestershire. He was at Prestwold Hall, a large country estate north of Leicester, at that time held by the Packe family. Three of Joseph’s children were baptised in the Church of St Andrew within the estate grounds so it is fair to assume he worked there as a gardener. It is also likely that he had been working in other locations before coming to Prestwold Hall; it is hard to imagine going straight from the tiny village of Maer to a grand estate over fifty miles away.

At Prestwold Joseph had three children; his daughter Elizabeth was born in 1802, followed by his sons James in 1804 and William in 1805. The name of the three children’s mother is recorded as ‘Mary’ but there is scant information about who she might be*. Elizabeth Myatt’s baptism record from 1802 states that she was ‘base-born’ (parents unmarried). It is probable that Joseph had never married Mary; there is no known record of Joseph Myatt marrying a woman named Mary between 1802 and 1805. However, James' and William's birth registers do not mention their being illegitimate.

It would appear that Mary, the mother of Joseph's children, died some time after her third child was born in 1805. Her oldest child Elizabeth may also have died by then; no records of Mary or Elizabeth have been found after 1805.

*See 'ABOUT' for more details.

Prestwold Hall. St Andrew’s Church is seen to the left of the house.

As shown on the baptism register, Joseph Myatt’s father was also called Joseph. This (father) Joseph Myatt was baptised in Maer in 1746. Joseph's mother Ann Bailey was about ten years younger than her husband; she was baptised at Maer in 1756. Joseph and Ann married in 1769. Ann may have been born a year or two before her baptism, but she was still probably only fifteen or sixteen when she married and her oldest son Joseph was born. This young age for starting a family was not unusual for that period. Other children baptised in St Peter’s at Maer who had a father named Joseph Myatt are William (born in 1772), Benjamin (1776), Elizabeth (1779), John (1781), Mary (1785), James (1786), Catherine (1789) and Margaret (1793). It is probable that these were Joseph Myatt’s siblings; John Myatt, for one, did have a connection with Joseph later in life.

Nothing is currently known of Joseph Myatt’s early life in Staffordshire but it can be assumed that he was raised in that rural village setting since so many younger siblings were born there. Joseph could read and write and later conduct business so he must have received an education – by no means guaranteed in those days. We can assume that Joseph started working as a gardener near Maer.

Joseph Myatt later worked on the gardens of large country estates before starting his own market gardening enterprise, so we can speculate that his early work involved the production of fruit and vegetables as well as aesthetic gardening. Unfortunately there are no records of his work prior to the age of thirty.

PRESTWOLD HALL, LEICESTERSHIRE

By 1802 when he was thirty years old Joseph Myatt was living in Leicestershire. He was at Prestwold Hall, a large country estate north of Leicester, at that time held by the Packe family. Three of Joseph’s children were baptised in the Church of St Andrew within the estate grounds so it is fair to assume he worked there as a gardener. It is also likely that he had been working in other locations before coming to Prestwold Hall; it is hard to imagine going straight from the tiny village of Maer to a grand estate over fifty miles away.

At Prestwold Joseph had three children; his daughter Elizabeth was born in 1802, followed by his sons James in 1804 and William in 1805. The name of the three children’s mother is recorded as ‘Mary’ but there is scant information about who she might be*. Elizabeth Myatt’s baptism record from 1802 states that she was ‘base-born’ (parents unmarried). It is probable that Joseph had never married Mary; there is no known record of Joseph Myatt marrying a woman named Mary between 1802 and 1805. However, James' and William's birth registers do not mention their being illegitimate.

It would appear that Mary, the mother of Joseph's children, died some time after her third child was born in 1805. Her oldest child Elizabeth may also have died by then; no records of Mary or Elizabeth have been found after 1805.

*See 'ABOUT' for more details.

Prestwold Hall. St Andrew’s Church is seen to the left of the house.

MARRIAGE TO SARAH

Joseph's residence between 1806 and 1809 is not known. He was now the unmarried father of two infant sons. There is some evidence that he moved back to Staffordshire where there was family support to care for his children. Now in his mid-thirties, he married a woman named Sarah*. At this time, the boys James and William were both under five-years-old; Sarah must have been a generous and loving person to take on the task of raising them.

*Sarah may have been Sarah Allcock. See 'ABOUT' for more details.

ROSEHILL PARK, SUSSEX

The Myatt family moved south; from 1809 Joseph was employed at Rosehill Park in East Sussex. (Today Rosehill is known as Brightling Park.) Joseph Myatt was presumably the head gardener at Rosehill Park because estate records show that every week he was given a sum of money to pay for garden labour. His own wages were forty pounds per half-year, quite a large sum for that time. We can safely assume that he had been working as a gardener for many years, at Prestwold Hall and elsewhere, in order to be given the prestigious job of head gardener at such a large estate as Rosehill Park.

Joseph and Sarah Myatt would have lived with the children James and William in the head gardener’s cottage at Rosehill Park. In 1810 they had a daughter called Eliza. She was baptised in the Church of St Thomas a Becket on the estate.

Rosehill Park was then the home of John Fuller III, the MP for East Sussex. Fuller called himself ‘Honest Jack’ but he was also known as ‘Mad Jack’ because of his eccentric and philanthropic ways. Fuller was very wealthy, a bachelor and a larger-than-life character. He was a well-connected and generous patron of the arts and science; he was a sponsor of the Royal Institution and he was a personal friend and patron of many politicians, academics, scientists, writers, musicians and artists. Among Fuller’s many notable friends was JMW Turner who often stayed at Rosehill Park and sketched and painted several views of the estate in the period that Joseph Myatt worked there.

Rosehill Park by JMW Turner. There is a gardener’s barrow and rake in the foreground. (Tate Museum)

Joseph's residence between 1806 and 1809 is not known. He was now the unmarried father of two infant sons. There is some evidence that he moved back to Staffordshire where there was family support to care for his children. Now in his mid-thirties, he married a woman named Sarah*. At this time, the boys James and William were both under five-years-old; Sarah must have been a generous and loving person to take on the task of raising them.

*Sarah may have been Sarah Allcock. See 'ABOUT' for more details.

ROSEHILL PARK, SUSSEX

The Myatt family moved south; from 1809 Joseph was employed at Rosehill Park in East Sussex. (Today Rosehill is known as Brightling Park.) Joseph Myatt was presumably the head gardener at Rosehill Park because estate records show that every week he was given a sum of money to pay for garden labour. His own wages were forty pounds per half-year, quite a large sum for that time. We can safely assume that he had been working as a gardener for many years, at Prestwold Hall and elsewhere, in order to be given the prestigious job of head gardener at such a large estate as Rosehill Park.

Joseph and Sarah Myatt would have lived with the children James and William in the head gardener’s cottage at Rosehill Park. In 1810 they had a daughter called Eliza. She was baptised in the Church of St Thomas a Becket on the estate.

Rosehill Park was then the home of John Fuller III, the MP for East Sussex. Fuller called himself ‘Honest Jack’ but he was also known as ‘Mad Jack’ because of his eccentric and philanthropic ways. Fuller was very wealthy, a bachelor and a larger-than-life character. He was a well-connected and generous patron of the arts and science; he was a sponsor of the Royal Institution and he was a personal friend and patron of many politicians, academics, scientists, writers, musicians and artists. Among Fuller’s many notable friends was JMW Turner who often stayed at Rosehill Park and sketched and painted several views of the estate in the period that Joseph Myatt worked there.

Rosehill Park by JMW Turner. There is a gardener’s barrow and rake in the foreground. (Tate Museum)

Gardening and landscaping were among John Fuller’s many interests. He was related by marriage to Capability Brown the most famous English landscaper of the day. The period that Joseph Myatt worked at Rosehill Park coincided with the large-scale shift in English landscape gardening from the formal European-style to the more naturalistic pastoral style. Major changes were made to the grounds at Rosehill, including the extravagant additions of a pyramid, an obelisk, a classical temple and a huge wall costing ten-thousand pounds that enclosed the entire 3,780 acres. The job of head gardener must have been a challenging one during this dynamic period.

John Fuller also owned numerous plantations in Jamaica. Estate records show that Joseph earned extra money for “work on the plantations”. It is not known whether Joseph actually spent time in Jamaica; shipping records that could prove this have not been found. Perhaps he simply worked on improvements to plantation crops in a greenhouse in Sussex.

MOVING ON IN AN ERA OF CHANGE

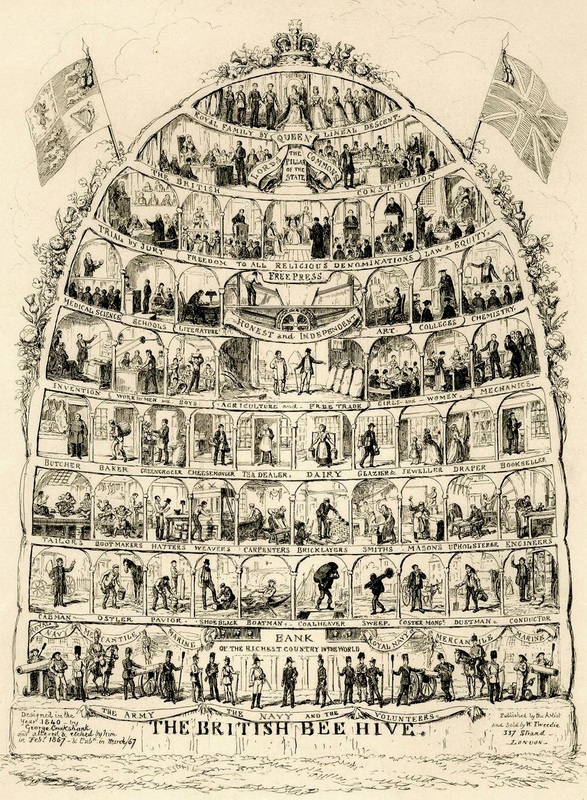

The nineteenth century saw the rise of the middle class in British society. Whereas in the past land held by the nobility was the only real source of wealth and power, industrial development and the growing capitalist economy meant that many more people could now get ahead through skill, education, hard work and enterprise. Joseph Myatt was clearly a man of vision, determination and ambition who suited this new social outlook. He was prepared to move considerable distances to take on new opportunities; we know he worked at Prestwold Hall and Rosehill Park, but there must have been other gardening jobs in other parts of the country in the periods unaccounted for. He had progressed to a position of responsibility and leadership on a grand estate far from the tiny Staffordshire village of his humble childhood. He had developed valuable horticultural skills and business experience which would enable him to make his own fortune. Rosehill Park records show that he already had a nice little sideline income fattening up hogs in his cottage garden; he received six pounds for two hogs in 1814. Joseph decided to stop working for other people and become a self-employed market gardener. He left Rosehill Park in 1814 to take his chance on a large scale: growing fruit and vegetables for the great produce markets of London.

‘The British Bee Hive’, a cartoon from 1840 by George Cruickshank held by the V&A Museum. It depicts the hierarchy of British social classes, from Royal Family at the top to dustman and chimneysweep at the bottom, with various levels of the new ‘middle class’ in between. The large panel in the centre shows ‘agriculture and free trade’, an area in which Joseph Myatt was ready to thrive.

John Fuller also owned numerous plantations in Jamaica. Estate records show that Joseph earned extra money for “work on the plantations”. It is not known whether Joseph actually spent time in Jamaica; shipping records that could prove this have not been found. Perhaps he simply worked on improvements to plantation crops in a greenhouse in Sussex.

MOVING ON IN AN ERA OF CHANGE

The nineteenth century saw the rise of the middle class in British society. Whereas in the past land held by the nobility was the only real source of wealth and power, industrial development and the growing capitalist economy meant that many more people could now get ahead through skill, education, hard work and enterprise. Joseph Myatt was clearly a man of vision, determination and ambition who suited this new social outlook. He was prepared to move considerable distances to take on new opportunities; we know he worked at Prestwold Hall and Rosehill Park, but there must have been other gardening jobs in other parts of the country in the periods unaccounted for. He had progressed to a position of responsibility and leadership on a grand estate far from the tiny Staffordshire village of his humble childhood. He had developed valuable horticultural skills and business experience which would enable him to make his own fortune. Rosehill Park records show that he already had a nice little sideline income fattening up hogs in his cottage garden; he received six pounds for two hogs in 1814. Joseph decided to stop working for other people and become a self-employed market gardener. He left Rosehill Park in 1814 to take his chance on a large scale: growing fruit and vegetables for the great produce markets of London.

‘The British Bee Hive’, a cartoon from 1840 by George Cruickshank held by the V&A Museum. It depicts the hierarchy of British social classes, from Royal Family at the top to dustman and chimneysweep at the bottom, with various levels of the new ‘middle class’ in between. The large panel in the centre shows ‘agriculture and free trade’, an area in which Joseph Myatt was ready to thrive.

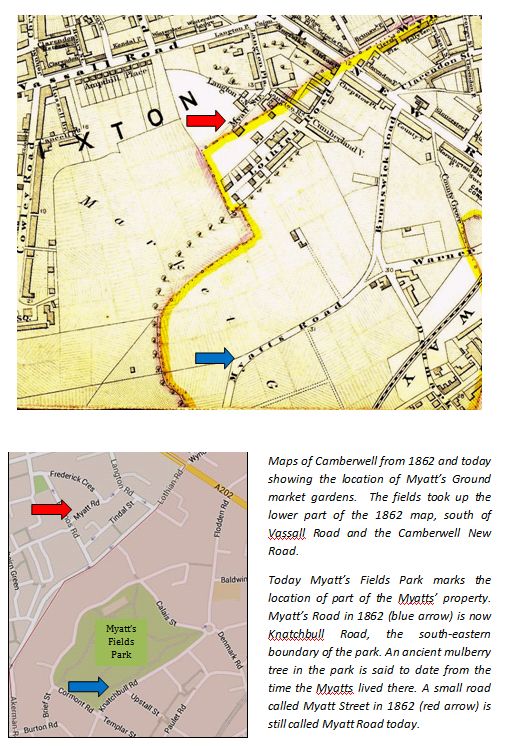

MYATT’S GROUND, CAMBERWELL

Joseph and Sarah Myatt and their children moved to Camberwell in Surrey, then on the south-eastern outskirts of London. Here, at the age of about forty-five, Joseph established his own market garden business. The property Joseph rented at Camberwell soon became known as Myatt’s Ground. (It was sometimes referred to as being located in Loughborough, then a small hamlet adjacent to the main part of Camberwell.) Joseph grew a large range of vegetables and fruit which he sold at the London Borough Market. As well as producing standard varieties, he put his years of experience in plant propagation to good use. In the 1820s he developed several new varieties of vegetables and fruits. These he gave the Myatt name: examples are the ‘Myatt Keeping-Onion’, the ‘Myatt Cabbage’ and the ‘Myatt Early Prolific Potato’.

Quite late in life, Joseph and Sarah had another child, a son named Joseph Jr, who was baptised at St Giles, Camberwell in 1821. By the time of his youngest child’s birth Joseph Myatt was approaching his fiftieth year. All three of his sons – James, William and Joseph Jr – were to become market gardeners. The two oldest, James and William, were now seventeen and sixteen years old, so presumably they had already become involved in the family business at Camberwell.

At this stage, Joseph Myatt’s younger brother John Myatt had left Staffordshire and was living nearby in Camberwell and working as a tailor. John’s eighth child Cerina Myatt was baptised alongside her cousin Joseph at St Giles.

Joseph and Sarah Myatt and their children moved to Camberwell in Surrey, then on the south-eastern outskirts of London. Here, at the age of about forty-five, Joseph established his own market garden business. The property Joseph rented at Camberwell soon became known as Myatt’s Ground. (It was sometimes referred to as being located in Loughborough, then a small hamlet adjacent to the main part of Camberwell.) Joseph grew a large range of vegetables and fruit which he sold at the London Borough Market. As well as producing standard varieties, he put his years of experience in plant propagation to good use. In the 1820s he developed several new varieties of vegetables and fruits. These he gave the Myatt name: examples are the ‘Myatt Keeping-Onion’, the ‘Myatt Cabbage’ and the ‘Myatt Early Prolific Potato’.

Quite late in life, Joseph and Sarah had another child, a son named Joseph Jr, who was baptised at St Giles, Camberwell in 1821. By the time of his youngest child’s birth Joseph Myatt was approaching his fiftieth year. All three of his sons – James, William and Joseph Jr – were to become market gardeners. The two oldest, James and William, were now seventeen and sixteen years old, so presumably they had already become involved in the family business at Camberwell.

At this stage, Joseph Myatt’s younger brother John Myatt had left Staffordshire and was living nearby in Camberwell and working as a tailor. John’s eighth child Cerina Myatt was baptised alongside her cousin Joseph at St Giles.

A nineteenth century watercolour of the house at Myatt's Ground, Camberwell.

(Stannard's 1862 maps here and following are taken from the British Library archive. Other maps from Google.)

RHUBARB

It was at Camberwell that Joseph began to experiment with growing rhubarb. Having established a profitable business and achieved success with new plant varieties he must have felt emboldened to further extend his business acumen and horticultural talents.

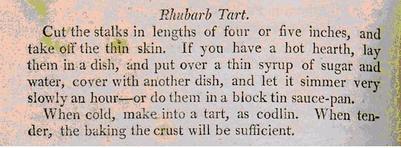

In the early nineteenth century rhubarb was not known as a food, but an expensive medicine called ‘physic’ sold by apothecaries. It was grown in Russia and Turkey where the roots were dried and powdered for use as a laxative. Around 1800 some English people had started to grow edible rhubarb; cultivating exotic plants was a common hobby among wealthy gentlemen. One of the first known references to rhubarb as a food is a tart recipe from Maria Elizabeth Rundell’s 1807 cookbook, reprinted in Alan Davidson’s Oxford Companion to Food.

RHUBARB

It was at Camberwell that Joseph began to experiment with growing rhubarb. Having established a profitable business and achieved success with new plant varieties he must have felt emboldened to further extend his business acumen and horticultural talents.

In the early nineteenth century rhubarb was not known as a food, but an expensive medicine called ‘physic’ sold by apothecaries. It was grown in Russia and Turkey where the roots were dried and powdered for use as a laxative. Around 1800 some English people had started to grow edible rhubarb; cultivating exotic plants was a common hobby among wealthy gentlemen. One of the first known references to rhubarb as a food is a tart recipe from Maria Elizabeth Rundell’s 1807 cookbook, reprinted in Alan Davidson’s Oxford Companion to Food.

In 1815 gardeners at the Chelsea Physic Garden discovered by accident that if the rhubarb plant was covered and kept in darkness it produced sweeter, more tender shoots, so-called ‘forced rhubarb’. Another factor that started the change from medicinal plant to food was the arrival in England of cheaper and more accessible sugar imported from British colonies in the West Indies. Mary Eaton’s 1823 cookbook contained recipes for rhubarb tart, sherbet, soup, pie, pudding and sauce. The popularity of rhubarb was growing.

Joseph Myatt obtained a dozen rhubarb roots from his friend Isaac Oldacre. Mr Oldacre was an English gardener from Derbyshire who had risen to the position of gardener for the Emperor of Russia in St Petersburg. He had returned to England in 1814 bringing innovative gardening ideas and a supply of plants and seeds, including roots of Russian rhubarb. Mr Oldacre was now employed at the estate of the eminent botanist Sir Joseph Banks where he developed new methods for raising mushrooms in sheds and growing pineapples in hothouses. Isaac Oldacre and Joseph Myatt were the same age; perhaps they had worked together as gardeners at Prestwold Hall or elsewhere in years past.

Joseph Myatt’s first rhubarb crop at Camberwell was described as “of a kind imported from Russia, finer and much earlier growing than the puny variety cultivated by the Brentford growers for Covent Garden”. Experimenting with forced rhubarb, Joseph developed large plants with enhanced flavour and texture and different colours. Famously, in 1824 Joseph sent his sons, James and William, to the Borough Markets with five bunches of rhubarb, of which they sold only three. The next week they took ten bunches, all of which were sold. Some have said that they took a recipe for rhubarb tart with them to promote sales. It was reported at the time that Joseph was ridiculed by green-grocers and his fellow market gardeners as “the man who sold physic pies”. It must have seemed ludicrous then to willingly eat a laxative pie. One green-grocer reportedly told Joseph’s sons that their previously esteemed father had taken leave of his senses. Joseph persisted with optimism. His positive attitude and intuition paid off; before long, rhubarb had become a favourite dessert on Victorian tables. Rhubarb production at Myatt’s Ground increased year by year.

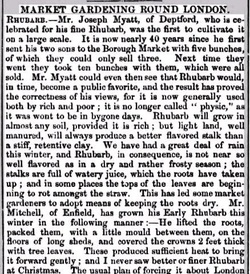

In 1851 The Irish Industrial Journal described the important role Joseph Myatt had in introducing edible rhubarb to Britain: (This newspaper article and all that follow are taken from the British Library archive.)

Joseph Myatt obtained a dozen rhubarb roots from his friend Isaac Oldacre. Mr Oldacre was an English gardener from Derbyshire who had risen to the position of gardener for the Emperor of Russia in St Petersburg. He had returned to England in 1814 bringing innovative gardening ideas and a supply of plants and seeds, including roots of Russian rhubarb. Mr Oldacre was now employed at the estate of the eminent botanist Sir Joseph Banks where he developed new methods for raising mushrooms in sheds and growing pineapples in hothouses. Isaac Oldacre and Joseph Myatt were the same age; perhaps they had worked together as gardeners at Prestwold Hall or elsewhere in years past.

Joseph Myatt’s first rhubarb crop at Camberwell was described as “of a kind imported from Russia, finer and much earlier growing than the puny variety cultivated by the Brentford growers for Covent Garden”. Experimenting with forced rhubarb, Joseph developed large plants with enhanced flavour and texture and different colours. Famously, in 1824 Joseph sent his sons, James and William, to the Borough Markets with five bunches of rhubarb, of which they sold only three. The next week they took ten bunches, all of which were sold. Some have said that they took a recipe for rhubarb tart with them to promote sales. It was reported at the time that Joseph was ridiculed by green-grocers and his fellow market gardeners as “the man who sold physic pies”. It must have seemed ludicrous then to willingly eat a laxative pie. One green-grocer reportedly told Joseph’s sons that their previously esteemed father had taken leave of his senses. Joseph persisted with optimism. His positive attitude and intuition paid off; before long, rhubarb had become a favourite dessert on Victorian tables. Rhubarb production at Myatt’s Ground increased year by year.

In 1851 The Irish Industrial Journal described the important role Joseph Myatt had in introducing edible rhubarb to Britain: (This newspaper article and all that follow are taken from the British Library archive.)

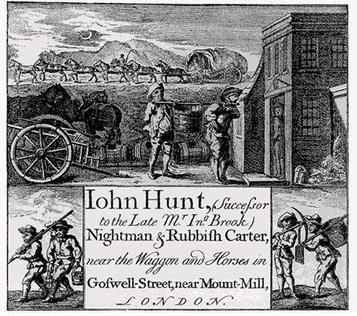

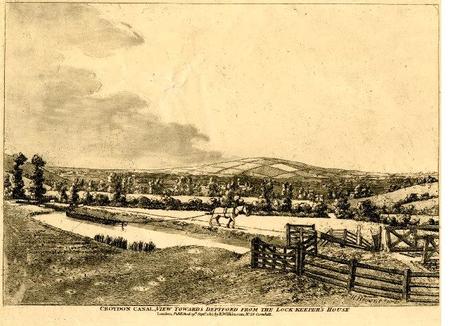

One key component of producing forced rhubarb was a plentiful supply of manure. This was provided by the ‘nightsoil’ carts which collected human waste from London’s cesspools and privies and distributed it to market gardeners on the outskirts of the city. An advertisement for London nightsoil deliveries is shown. Another aspect of successful gardening was the plentiful supply of water. At this time the market garden lands south of the Thames were serviced by a considerable network of canals. These were built primarily for transporting goods, but also provided water for agriculture. The following illustration is Croydon Canal, View Towards Deptford. 1815 (British Museum). Croydon Canal was a branch of the Grand Surrey Canal which ran from Camberwell to the Thames at Rotherhithe.

After about ten years at Camberwell, Joseph Myatt was still ambitious to further his success and create better opportunities for his sons. He left his oldest son James at Myatt’s Ground and moved about three miles east to a larger property called Manor Farm at Deptford in Kent.

James, who was now in his mid-twenties, stayed on at Camberwell and continued to run the market garden at Myatt’s Ground while the rest of his family moved on. James Myatt married Sarah Martin in 1828 and started a family. James and then his own sons worked at Myatt's Ground until 1870. Joseph Myatt is associated with the history of Camberwell for establishing that property and his work on rhubarb cultivation there, but he only lived there for about ten years. It was James Myatt who stayed at Camberwell, working that land for over forty years.

MANOR FARM, DEPTFORD

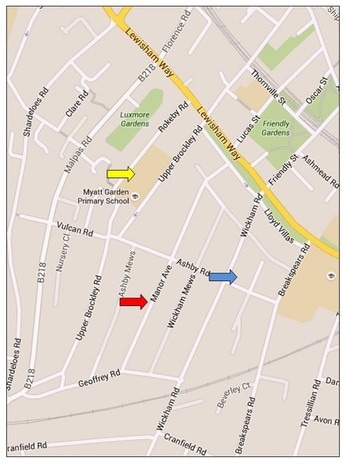

By 1827 Joseph Myatt had re-established himself at Manor Farm . He named his business ‘Joseph Myatt and Sons’. The Deptford Tithe Map of 1844 shows Manor Farm encompassed over 80 acres of ground. (The location was sometimes referred to as Brockley or Loampit Hill.)

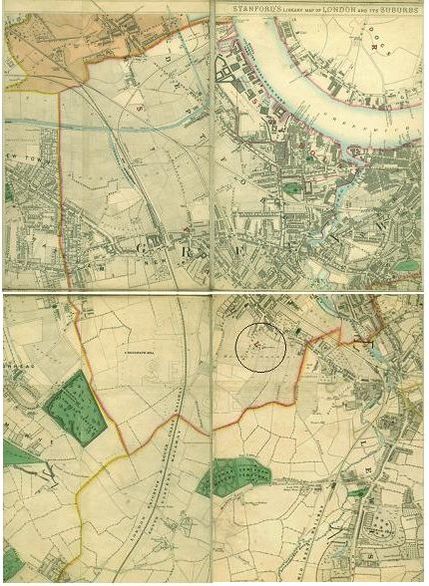

Four parts of an 1862 map of London show the Thames at Greenwich (top right) and Deptford (centre). Manor Farm is circled, with the fields occupying the surrounding shaded area. The large green patch on the left is Nunhead Cemetery. The two north-south railway lines on this map were new in 1862 and did not exist during Joseph Myatt’s lifetime, but the suburban line through Deptford was a boon to Manor Farm when it opened in 1836.

James, who was now in his mid-twenties, stayed on at Camberwell and continued to run the market garden at Myatt’s Ground while the rest of his family moved on. James Myatt married Sarah Martin in 1828 and started a family. James and then his own sons worked at Myatt's Ground until 1870. Joseph Myatt is associated with the history of Camberwell for establishing that property and his work on rhubarb cultivation there, but he only lived there for about ten years. It was James Myatt who stayed at Camberwell, working that land for over forty years.

MANOR FARM, DEPTFORD

By 1827 Joseph Myatt had re-established himself at Manor Farm . He named his business ‘Joseph Myatt and Sons’. The Deptford Tithe Map of 1844 shows Manor Farm encompassed over 80 acres of ground. (The location was sometimes referred to as Brockley or Loampit Hill.)

Four parts of an 1862 map of London show the Thames at Greenwich (top right) and Deptford (centre). Manor Farm is circled, with the fields occupying the surrounding shaded area. The large green patch on the left is Nunhead Cemetery. The two north-south railway lines on this map were new in 1862 and did not exist during Joseph Myatt’s lifetime, but the suburban line through Deptford was a boon to Manor Farm when it opened in 1836.

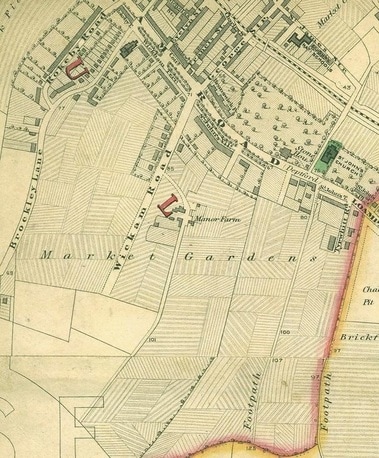

A closer view of the 1862 London map. Manor Farm occupied a large area south of Lewisham Road between Brockley Lane and a chalk pit and brick fields. The Manor Farm buildings can be seen on the eastern side of Wickam Road. The same section of Deptford today shows street names from 1862 remain. The original location of the farm buildings is between Wickham and Breakspears Roads (blue arrow). Myatt Garden Primary School (yellow arrow) and Manor Avenue (red arrow) honour history.

THE MYATT FAMILY AT MANOR FARM

Joseph’s daughter Eliza Myatt married Henry Sheppard in 1828. The Sheppard family were also market gardeners with close ties to the Myatts; Henry's uncle was Joseph’s good friend and neighbour at Deptford, Samuel Sheppard. Henry's father Henry Sheppard Sr ran a market garden with Joseph Myatt as a financial partner. Eliza and Henry were both under-aged in 1828 – she was only eighteen – but their marriage record shows permission was given by their fathers. Eliza and Henry Sheppard moved to his father's market garden at Bermondsey and started a family.

With James staying back at Myatt's Ground and Eliza married, Joseph and Sarah Myatt now lived at Manor Farm with their adult son William and young Joseph Jr.

In 1832 Joseph’s wife Sarah Myatt died, aged in her late fifties. She was buried in the grounds of St Paul’s Churchyard in Deptford.

William Myatt married Eleanor Brown in 1833 and started his own family, staying on at Manor Farm with his father.

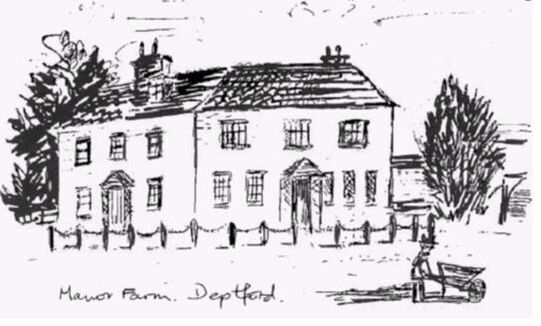

Two impressions of Manor Farm and Deptford: a sketch by Brenda Payne and a nineteenth century print of Deptford Common.

Joseph’s daughter Eliza Myatt married Henry Sheppard in 1828. The Sheppard family were also market gardeners with close ties to the Myatts; Henry's uncle was Joseph’s good friend and neighbour at Deptford, Samuel Sheppard. Henry's father Henry Sheppard Sr ran a market garden with Joseph Myatt as a financial partner. Eliza and Henry were both under-aged in 1828 – she was only eighteen – but their marriage record shows permission was given by their fathers. Eliza and Henry Sheppard moved to his father's market garden at Bermondsey and started a family.

With James staying back at Myatt's Ground and Eliza married, Joseph and Sarah Myatt now lived at Manor Farm with their adult son William and young Joseph Jr.

In 1832 Joseph’s wife Sarah Myatt died, aged in her late fifties. She was buried in the grounds of St Paul’s Churchyard in Deptford.

William Myatt married Eleanor Brown in 1833 and started his own family, staying on at Manor Farm with his father.

Two impressions of Manor Farm and Deptford: a sketch by Brenda Payne and a nineteenth century print of Deptford Common.

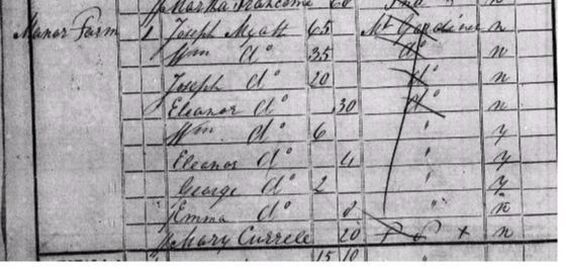

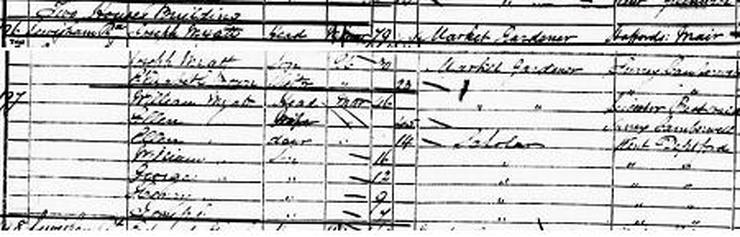

The 1841 census for Manor Farm showing Joseph, then a widower, living with his sons William (35) and Joseph (20), William’s wife Eleanor (30) and the first four of their six children, as well as a servant. Joseph’s age shown here - 65 - is incorrect; he was 69.

Later in the 1840s, the large farmhouse at Manor Farm was divided into two. Joseph Myatt who was now a widower, lived in one half of the house with his unmarried youngest son Joseph Jr, while William Myatt and his wife Eleanor occupied the other half with their children. Eleanor's cousin, Elizabeth Brown came to live with Joseph as his housekeeper.

The 1851 census for Manor Farm noted that it was now a 'two house building'. Joseph's household is shown at the top, and William's household below. Elizabeth Brown aged 25 was shown as a 'visitor' staying with Joseph (4th line). In fact, Elizabeth Brown lived with the Myatt family all her adult life, being housekeeper for Joseph after Sarah had died and later housekeeper for William after Eleanor died. When William Myatt died, his late wife's cousin Elizabeth Brown was a major beneficiary of his will.

The 1851 census for Manor Farm noted that it was now a 'two house building'. Joseph's household is shown at the top, and William's household below. Elizabeth Brown aged 25 was shown as a 'visitor' staying with Joseph (4th line). In fact, Elizabeth Brown lived with the Myatt family all her adult life, being housekeeper for Joseph after Sarah had died and later housekeeper for William after Eleanor died. When William Myatt died, his late wife's cousin Elizabeth Brown was a major beneficiary of his will.

STRAWBERRIES

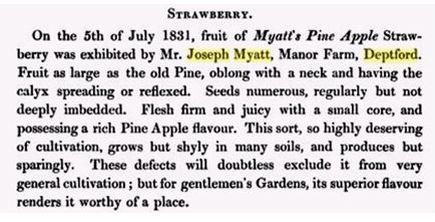

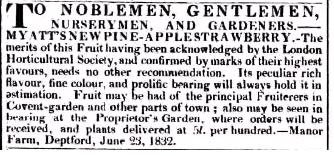

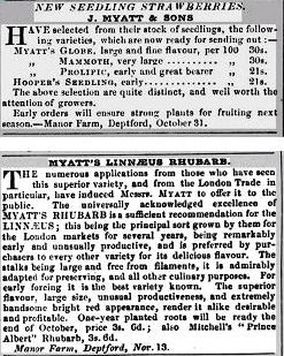

Not one to rest on his laurels, around the time he moved to Deptford Joseph Myatt embarked on a new specialisation: strawberries. It was as a strawberry producer that Joseph Myatt was to achieve real fame in his lifetime. Strawberry cultivation was relatively new in 1830; prior to this time strawberries were eaten only as a very small fruit picked where they grew in the wild. Like rhubarb, the popularity of strawberries in England was enhanced by rapid growth in the importation of sugar. In those days jam-making was a good way to enjoy the taste of fruit year-round and now it had become much more affordable. Market gardeners were still experimenting with the development of hybrid strawberries that were large, sweet and prolific enough to warrant commercial production. Of all the experimental work done at Manor Farm, the most successful was the development of new varieties of strawberries. In 1831 Joseph introduced his new ‘Pine-Apple Strawberry’ also known as ‘Myatt’s Pine’. It was immediately highly regarded by horticultural writers of the day for its sweet flavour and large size. Joseph won a Banksian Medal in 1832 for his ‘Pine-Apple Strawberry’. The next excerpt from a report of the Horticultural Society of London in 1831 shows that Joseph achieved rapid success with his new strawberry. The following advertisement from the Morning Post of 25th June, 1832 is another indication of Joseph’s success with strawberries, selling strawberry plants to gardeners.

Not one to rest on his laurels, around the time he moved to Deptford Joseph Myatt embarked on a new specialisation: strawberries. It was as a strawberry producer that Joseph Myatt was to achieve real fame in his lifetime. Strawberry cultivation was relatively new in 1830; prior to this time strawberries were eaten only as a very small fruit picked where they grew in the wild. Like rhubarb, the popularity of strawberries in England was enhanced by rapid growth in the importation of sugar. In those days jam-making was a good way to enjoy the taste of fruit year-round and now it had become much more affordable. Market gardeners were still experimenting with the development of hybrid strawberries that were large, sweet and prolific enough to warrant commercial production. Of all the experimental work done at Manor Farm, the most successful was the development of new varieties of strawberries. In 1831 Joseph introduced his new ‘Pine-Apple Strawberry’ also known as ‘Myatt’s Pine’. It was immediately highly regarded by horticultural writers of the day for its sweet flavour and large size. Joseph won a Banksian Medal in 1832 for his ‘Pine-Apple Strawberry’. The next excerpt from a report of the Horticultural Society of London in 1831 shows that Joseph achieved rapid success with his new strawberry. The following advertisement from the Morning Post of 25th June, 1832 is another indication of Joseph’s success with strawberries, selling strawberry plants to gardeners.

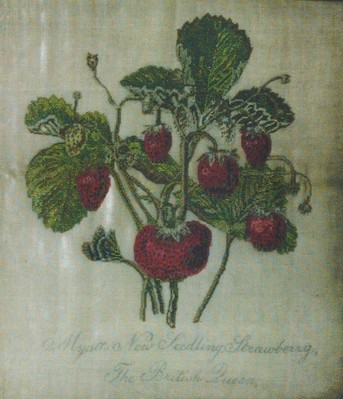

Other strawberry varieties were developed by Joseph Myatt in the years ahead. These included ‘Eliza’ (1836) named after his daughter, ‘British Queen’ (1841) patriotically named in honour of Queen Victoria, ‘Deptford Pine’ (1843) and ‘Alice Maud’ (1844) presumably named after Queen Victoria’s baby daughter. Of these, the most prominent success came with the development of the ‘British Queen’ in 1841. It was an immediate favourite and went on to dominate the commercial market throughout Victorian times. The well-known horticulturalist and writer Edward Bunyard considered it to be among the best flavoured as late as 1914. ‘British Queen’ attracted considerable attention as the first large-fruited hybrid. A number of claims of extremely large fruit were made in The Gardeners Chronicle. On the 13th of September, 1845 it reported: “…the biggest being a single fruit of two and a half ounces, with a circumference of nine and a half inches. The hybrid origin is Fragaria chiloensis.” The following illustration of the 'British Queen' is from an 1850 Belgian publication, Album de Pomologie.

Two contemporary descriptions of the ‘British Queen’ detail its appearance and flavour:

“Fruit large, sometimes very large, roundish, flattened, and cockscomb shaped, the smaller fruit ovate or conical. Skin pale red, colouring unequally, being frequently white or greenish-white at the apex. Flesh white, firm, juicy, and with a remarkably rich and exquisite flavour.” [Hogg – Fruit Manual 1860]

“This is perhaps the most famous strawberry ever raised in England, and has been very widely grown there, where it is a favourite market berry. Unfortunately, it does not come to full perfection here; and it is not only tender, but very capricious in its choice of soils. It is the parent of many excellent kinds. Fruit of the largest size, roundish, slightly conical, rich scarlet; flesh pure white, and of the highest flavour. Forces admirably.” [The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste USA 1852]

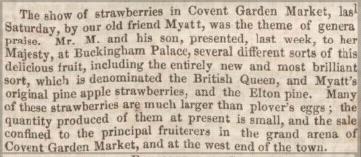

Joseph received several awards and medals for his endeavours in strawberry production from the Horticultural Society of London, later renamed the Royal Horticultural Society. He was honoured with a letter of commendation and a silver medal from the Prince Consort Albert for the excellence of his strawberries. He also received a silver kettle in thanks for the ‘British Queen’ strawberries he took as a gift to Buckingham Palace. This article mentioning the occasion appeared in the West Kent Guardian in July 1840, a year before ‘British Queen’ strawberries were released to the public:

“Fruit large, sometimes very large, roundish, flattened, and cockscomb shaped, the smaller fruit ovate or conical. Skin pale red, colouring unequally, being frequently white or greenish-white at the apex. Flesh white, firm, juicy, and with a remarkably rich and exquisite flavour.” [Hogg – Fruit Manual 1860]

“This is perhaps the most famous strawberry ever raised in England, and has been very widely grown there, where it is a favourite market berry. Unfortunately, it does not come to full perfection here; and it is not only tender, but very capricious in its choice of soils. It is the parent of many excellent kinds. Fruit of the largest size, roundish, slightly conical, rich scarlet; flesh pure white, and of the highest flavour. Forces admirably.” [The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste USA 1852]

Joseph received several awards and medals for his endeavours in strawberry production from the Horticultural Society of London, later renamed the Royal Horticultural Society. He was honoured with a letter of commendation and a silver medal from the Prince Consort Albert for the excellence of his strawberries. He also received a silver kettle in thanks for the ‘British Queen’ strawberries he took as a gift to Buckingham Palace. This article mentioning the occasion appeared in the West Kent Guardian in July 1840, a year before ‘British Queen’ strawberries were released to the public:

THE SUCCESS OF JOSEPH MYATT AND SONS

Sarah Myatt must have enjoyed watching her husband’s accomplishments in creating a prosperous business and his triumphant role in the introduction of rhubarb. She would also have seen his early success with strawberries, but could not have known the extent to which that part of the business would flourish after her death in 1832. Manor Farm expanded; in the 1861 census it was described as a market garden of “120 acres employing 37 men, 12 women and 10 boys”. While rhubarb and strawberries were a source of fame, Manor Farm continued to produce its wide variety of fruit and vegetables for the London market. The firm ‘Joseph Myatt and Sons’ not only prospered but developed an international reputation in gardening circles.

The expansion of the railways at this time allowed for wider and faster distribution of fresh produce. Deptford was on one of London’s first suburban railway lines, opened in 1836. Produce was now able to be sent beyond the city. One big customer for Myatt’s rhubarb was a Somerset wine-making company. Produce could also reach the London markets much more quickly; in the strawberry season berry pickers in the market gardens of Kent started work at 3am and loaded the fruit into railway carriages specially designed to convey strawberries. The berries were on display at the great London markets – "still glistening with dew" – a few hours later.

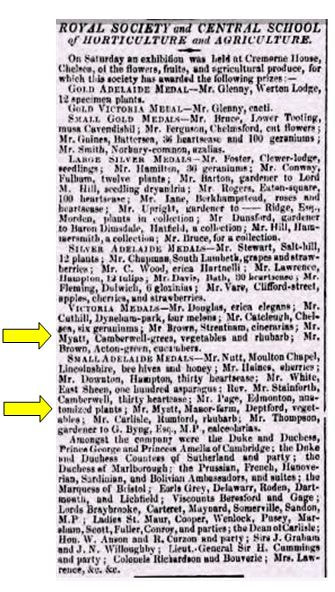

In the following article from the Morning Chronicle of 21st May, 1838 we see that back in Camberwell James was already making his own name in market gardening circles; he is competing with his own father for prizes at a Royal Society horticultural exhibition. Mr Myatt of Camberwell (James) won a Victoria medal while Mr Myatt of Deptford (Joseph) won an Adelaide medal. It is interesting to note that other gardeners were growing rhubarb by 1838 and one of them beat Mr Myatt for that prize.

Sarah Myatt must have enjoyed watching her husband’s accomplishments in creating a prosperous business and his triumphant role in the introduction of rhubarb. She would also have seen his early success with strawberries, but could not have known the extent to which that part of the business would flourish after her death in 1832. Manor Farm expanded; in the 1861 census it was described as a market garden of “120 acres employing 37 men, 12 women and 10 boys”. While rhubarb and strawberries were a source of fame, Manor Farm continued to produce its wide variety of fruit and vegetables for the London market. The firm ‘Joseph Myatt and Sons’ not only prospered but developed an international reputation in gardening circles.

The expansion of the railways at this time allowed for wider and faster distribution of fresh produce. Deptford was on one of London’s first suburban railway lines, opened in 1836. Produce was now able to be sent beyond the city. One big customer for Myatt’s rhubarb was a Somerset wine-making company. Produce could also reach the London markets much more quickly; in the strawberry season berry pickers in the market gardens of Kent started work at 3am and loaded the fruit into railway carriages specially designed to convey strawberries. The berries were on display at the great London markets – "still glistening with dew" – a few hours later.

In the following article from the Morning Chronicle of 21st May, 1838 we see that back in Camberwell James was already making his own name in market gardening circles; he is competing with his own father for prizes at a Royal Society horticultural exhibition. Mr Myatt of Camberwell (James) won a Victoria medal while Mr Myatt of Deptford (Joseph) won an Adelaide medal. It is interesting to note that other gardeners were growing rhubarb by 1838 and one of them beat Mr Myatt for that prize.

FAME AS A PIONEER OF RHUBARB

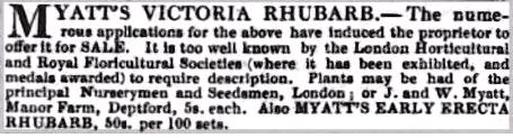

Rhubarb production was still underway on a large scale at Manor Farm; by the 1850s it had become a familiar fruit in British cuisine. At the height of the season a thousand bunches a day were coming off Manor Farm. Joseph Myatt experimented with different hybrids of rhubarb producing cultivars of differing colour and flavour. One stalk of Myatt’s famous ‘Victoria’ rhubarb was said to have weighed up to seven pounds. ‘Linnaeus’ was another successful variety, first released in 1842. Joseph also managed to produce his ‘Early Eracta’ rhubarb in late winter, a great sales and marketing coup. In those days fruit was very welcome in the cold months when few fresh foods were available. In addition to selling rhubarb for food, the Myatts sold rhubarb plants to commercial and home gardeners.

The Quarterly Review (vol 89) of 1851 described the increased popularity of rhubarb: “Mr. Joseph Myatt of Deptford, a most benevolent man now upwards of seventy years of age, was the first to cultivate rhubarb on a large scale. The foot-stalks of the physic-plant are now regarded as a necessary rather than a luxury in culinary management. The most frugal table can display its rhubarb pudding or tart, in season.”

This account of the development of rhubarb was written in 1875: “Of late years this has become a much sought-for and important vegetable, but half a century ago it was scarcely known in the London market. The late Mr. Myatt, of Deptford, is looked upon as being the father of Rhubarb growers. The Deptford and neighbouring market gardeners at first thought that Myatt was mad upon the subject; but they soon found out that this was a paying job, and consequently took to growing it, as did the majority of the London market gardeners. Now it is almost universally grown.”

The Gardener's Magazine and Register of Rural and Domestic (Volume 15) described Manor Farm rhubarb in 1838: “From Mr. Myatt of Deptford, stalks of a new kind of Rhubarb, called the Victoria. It appeared to be a variety of Rheum hybridum, of enormous size; the leafstalks were each 2 ft. 8 in. long, and 6 in. in circumference, and twelve of the stalks weighed 46 lb. Few vegetables have made a more rapid progress in their cultivation, within the past twenty years, than this article, and we yet expect to see it cultivated by the hundred acres and brought to our market in wagon loads. The edible kinds were first introduced in the London market by Mr. Myatt, about 20 years ago, and it is now in high demand. Myatt's Victoria is an earlier kind than the Giant, very richly flavored, and generally superior to the large Early Red, and is a seedling from the Victoria, by Buist. Large Early Red is a seedling from the Victoria, and is eight days earlier, and larger than its parent, about three feet long; and as a general rule, the red stalk sorts are earlier than the green. Myatt's Linnaeus is the largest and best Rhubarb known. It maintains its colour after being cooked, and requires less sugar than other sorts. Many of the Rhubarbs form a mass or magma by cooking, but the Myatt's Linnaeus scarcely changes its figure, and is still more tender and less stringy than any of the other sorts. It was introduced into this country [America] by the Hon. Marshall P. Wilder, of Boston, and its seeds have the peculiar property of producing their kind more regularly than other sorts.”

Working Farmer, an American publication, described Myatt's 'Victoria' and ' Linnaeus' rhubarb for seed sales to growers: “Myatt’s Victoria has been so generally introduced, and has given such satisfaction to all who possess it, that it will be difficult to displace it by other new kinds. Mr. Myatt, the raiser of this fine kind, has offered for sale, a new variety, and some others have also been produced. Myatt’s Linnaeus- This is the principal kind, grown by Messrs. Myatt, who raise immense quantities for the London market, for several years, and was not offered for sale, until after numerous applications from the London trade. It is remarkably early, and unusually productive, and is preferred by purchasers, to every other variety, for its delicious flavor. The stalks being large, and free from filaments, it is admirably adapted for preserving, and all other purposes. For early forcing, it is the best known. The superior flavor, large size, unusual productiveness, and extremely light red appearance, render it alike desirable and profitable.”

Another article from 1840 decried the exclusivity and rarity of Myatt’s seeds: “"Myatt's Victoria Rhubarb" was raised by a gardener near London, a year or two since. This is quite rare, as yet, and the roots are sold at a very high price. It is said that the seed of this variety will not produce the same kind. I could not learn that any person had raised any of it from seed, or that any of the seed was to be had.”

The next advertisement from the Morning Advertiser in 1838 shows that seedlings of the popular ‘Victoria’ rhubarb could indeed be purchased from Manor Farm, but the price of five shillings per plant did make it very expensive. Another Myatt variety ‘Early Erecta’ was sold at one shilling for two plants. Seed and seedling sales must have proven profitable because similar advertisements appeared more frequently in newspapers, examples being the following two taken from London’s South-East Gazette in 1846 and 1847.

Rhubarb production was still underway on a large scale at Manor Farm; by the 1850s it had become a familiar fruit in British cuisine. At the height of the season a thousand bunches a day were coming off Manor Farm. Joseph Myatt experimented with different hybrids of rhubarb producing cultivars of differing colour and flavour. One stalk of Myatt’s famous ‘Victoria’ rhubarb was said to have weighed up to seven pounds. ‘Linnaeus’ was another successful variety, first released in 1842. Joseph also managed to produce his ‘Early Eracta’ rhubarb in late winter, a great sales and marketing coup. In those days fruit was very welcome in the cold months when few fresh foods were available. In addition to selling rhubarb for food, the Myatts sold rhubarb plants to commercial and home gardeners.

The Quarterly Review (vol 89) of 1851 described the increased popularity of rhubarb: “Mr. Joseph Myatt of Deptford, a most benevolent man now upwards of seventy years of age, was the first to cultivate rhubarb on a large scale. The foot-stalks of the physic-plant are now regarded as a necessary rather than a luxury in culinary management. The most frugal table can display its rhubarb pudding or tart, in season.”

This account of the development of rhubarb was written in 1875: “Of late years this has become a much sought-for and important vegetable, but half a century ago it was scarcely known in the London market. The late Mr. Myatt, of Deptford, is looked upon as being the father of Rhubarb growers. The Deptford and neighbouring market gardeners at first thought that Myatt was mad upon the subject; but they soon found out that this was a paying job, and consequently took to growing it, as did the majority of the London market gardeners. Now it is almost universally grown.”

The Gardener's Magazine and Register of Rural and Domestic (Volume 15) described Manor Farm rhubarb in 1838: “From Mr. Myatt of Deptford, stalks of a new kind of Rhubarb, called the Victoria. It appeared to be a variety of Rheum hybridum, of enormous size; the leafstalks were each 2 ft. 8 in. long, and 6 in. in circumference, and twelve of the stalks weighed 46 lb. Few vegetables have made a more rapid progress in their cultivation, within the past twenty years, than this article, and we yet expect to see it cultivated by the hundred acres and brought to our market in wagon loads. The edible kinds were first introduced in the London market by Mr. Myatt, about 20 years ago, and it is now in high demand. Myatt's Victoria is an earlier kind than the Giant, very richly flavored, and generally superior to the large Early Red, and is a seedling from the Victoria, by Buist. Large Early Red is a seedling from the Victoria, and is eight days earlier, and larger than its parent, about three feet long; and as a general rule, the red stalk sorts are earlier than the green. Myatt's Linnaeus is the largest and best Rhubarb known. It maintains its colour after being cooked, and requires less sugar than other sorts. Many of the Rhubarbs form a mass or magma by cooking, but the Myatt's Linnaeus scarcely changes its figure, and is still more tender and less stringy than any of the other sorts. It was introduced into this country [America] by the Hon. Marshall P. Wilder, of Boston, and its seeds have the peculiar property of producing their kind more regularly than other sorts.”

Working Farmer, an American publication, described Myatt's 'Victoria' and ' Linnaeus' rhubarb for seed sales to growers: “Myatt’s Victoria has been so generally introduced, and has given such satisfaction to all who possess it, that it will be difficult to displace it by other new kinds. Mr. Myatt, the raiser of this fine kind, has offered for sale, a new variety, and some others have also been produced. Myatt’s Linnaeus- This is the principal kind, grown by Messrs. Myatt, who raise immense quantities for the London market, for several years, and was not offered for sale, until after numerous applications from the London trade. It is remarkably early, and unusually productive, and is preferred by purchasers, to every other variety, for its delicious flavor. The stalks being large, and free from filaments, it is admirably adapted for preserving, and all other purposes. For early forcing, it is the best known. The superior flavor, large size, unusual productiveness, and extremely light red appearance, render it alike desirable and profitable.”

Another article from 1840 decried the exclusivity and rarity of Myatt’s seeds: “"Myatt's Victoria Rhubarb" was raised by a gardener near London, a year or two since. This is quite rare, as yet, and the roots are sold at a very high price. It is said that the seed of this variety will not produce the same kind. I could not learn that any person had raised any of it from seed, or that any of the seed was to be had.”

The next advertisement from the Morning Advertiser in 1838 shows that seedlings of the popular ‘Victoria’ rhubarb could indeed be purchased from Manor Farm, but the price of five shillings per plant did make it very expensive. Another Myatt variety ‘Early Erecta’ was sold at one shilling for two plants. Seed and seedling sales must have proven profitable because similar advertisements appeared more frequently in newspapers, examples being the following two taken from London’s South-East Gazette in 1846 and 1847.

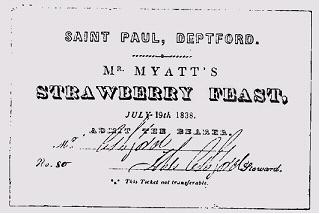

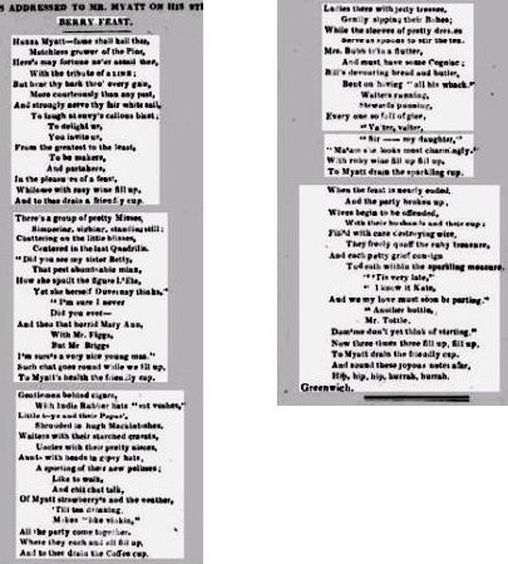

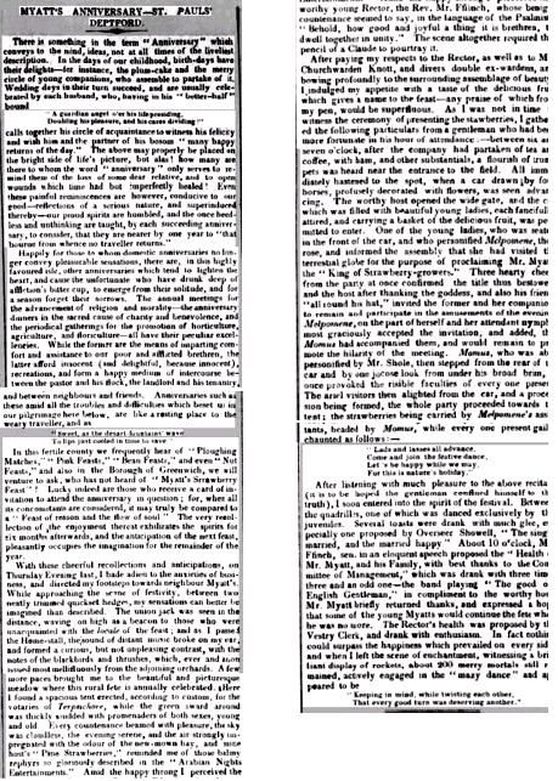

STRAWBERRY FEASTS

Manor Farm was well-known for its annual ‘Strawberry Feasts’. These took place in July when the business of harvesting the strawberries was at its height. The Strawberry Feasts were one of the social events of the year in Deptford and an admission ticket, issued by invitation only, was highly prized. There are vivid accounts of the feasts in the newspapers of the time, describing decorated farm carts carrying young girls dressed as Greek goddesses distributing baskets of strawberries, picnics, drinking, fireworks and dancing. Of course an added benefit of the Strawberry Feasts was the promotion of the famous Myatt Strawberry. It has been noted by a contemporary food historian that Joseph Myatt was “an enterprising and forward-looking man with an eye for the main chance”.

An invitation to one of the Strawberry Feasts, signed by the Manor Farm steward, and an embroidery of the British Queen, made by either Joseph's daughter Eliza, or one of his granddaughters.

Manor Farm was well-known for its annual ‘Strawberry Feasts’. These took place in July when the business of harvesting the strawberries was at its height. The Strawberry Feasts were one of the social events of the year in Deptford and an admission ticket, issued by invitation only, was highly prized. There are vivid accounts of the feasts in the newspapers of the time, describing decorated farm carts carrying young girls dressed as Greek goddesses distributing baskets of strawberries, picnics, drinking, fireworks and dancing. Of course an added benefit of the Strawberry Feasts was the promotion of the famous Myatt Strawberry. It has been noted by a contemporary food historian that Joseph Myatt was “an enterprising and forward-looking man with an eye for the main chance”.

An invitation to one of the Strawberry Feasts, signed by the Manor Farm steward, and an embroidery of the British Queen, made by either Joseph's daughter Eliza, or one of his granddaughters.

A poem printed in the Kentish Mercury in July 1837, celebrated the annual strawberry feast:

This rather florid description of the strawberry feast was printed in the Kentish Mercury in July of 1835:

ST PAUL'S PARISH

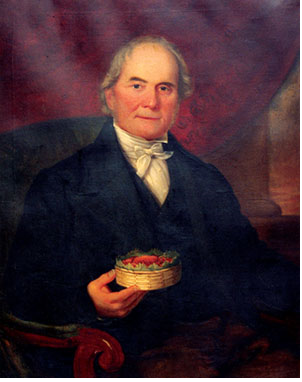

Joseph Myatt became a prominent citizen of Deptford. He had his portrait painted (by Williamson) around 1845. It shows a grey-haired smiling man, clean-shaven with the rosy complexion of someone used to working outdoors. He is holding a punnet of strawberries.

Joseph Myatt became a prominent citizen of Deptford. He had his portrait painted (by Williamson) around 1845. It shows a grey-haired smiling man, clean-shaven with the rosy complexion of someone used to working outdoors. He is holding a punnet of strawberries.

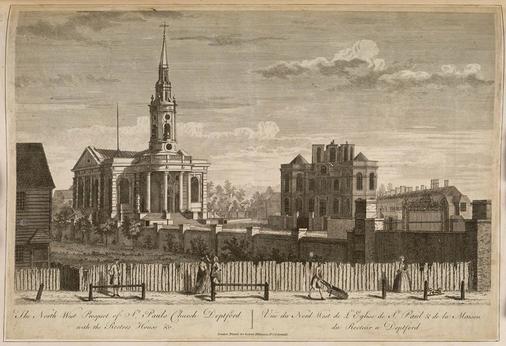

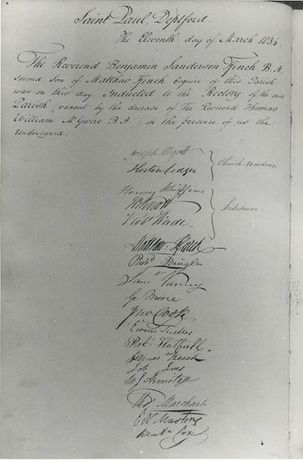

Joseph Myatt was a senior parishioner at St Paul’s Church in Deptford and held offices such as Churchwarden and Overseer of the Poor. In Victorian times, before the existence of local councils and social security, it was the churches that ran institutions within the parish and made decisions about local development, so these were important positions. Several times Joseph was called upon as an expert witness in trials at the Old Bailey that involved plant identification.

In the period that Joseph Myatt lived at Deptford the population of the parish of St Paul’s doubled. Maps of Camberwell and Deptford show the Myatts’ market gardens butted up against residential areas on what was then a rapidly expanding city. All across London, market gardens were being squeezed out by the expansion of the railways and the accompanying Victorian building boom. One can imagine the market gardeners’ despair at watching the growing city encroaching around them.

A view of St Paul’s Church, Deptford (Guildhall Library) and the 1834 induction of a new reverend at St Paul, showing the signature of Joseph Myatt, Church Warden. (top signature)

In the period that Joseph Myatt lived at Deptford the population of the parish of St Paul’s doubled. Maps of Camberwell and Deptford show the Myatts’ market gardens butted up against residential areas on what was then a rapidly expanding city. All across London, market gardens were being squeezed out by the expansion of the railways and the accompanying Victorian building boom. One can imagine the market gardeners’ despair at watching the growing city encroaching around them.

A view of St Paul’s Church, Deptford (Guildhall Library) and the 1834 induction of a new reverend at St Paul, showing the signature of Joseph Myatt, Church Warden. (top signature)

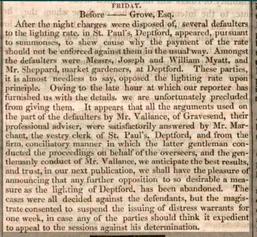

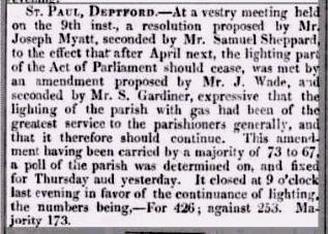

An insight to Joseph Myatt’s character is given by a controversy around modernisation in St Paul’s parish. In 1840 the proposed introduction of gas street lighting to Deptford became a devisive issue. Joseph was the most vocal among a group opposed. The local newspapers printed detailed arguments for and against gas lighting, with the chief objection being expense. The newspaper proprietors were clearly in favour of gas lighting; several amusing songs were published on the subject, naming and mocking Mr Myatt and his complaints. After a prolonged period of campaigning a vote was taken and gas lighting adopted. Mr Myatt was then named in the papers as a good sport in accepting defeat and he is even described joining in the singing at a celebratory parish dinner. However the next article reveals that a few months after it was agreed that gas lighting would be installed in Deptford, Joseph and William Myatt, along with Joseph's old friend Samuel Sheppard, were charged with refusing to pay the special lighting rates. In stating their case, they actually proposed that the decision be reversed, but were unsuccessful again. Two years later, when the gas lighting had been installed, Joseph Myatt and Samuel Sheppard were still leading a campaign in the parish for it to be abandoned. The tenacity that had enabled Joseph Myatt to become a successful businessman also clearly extended to other aspects of his life.

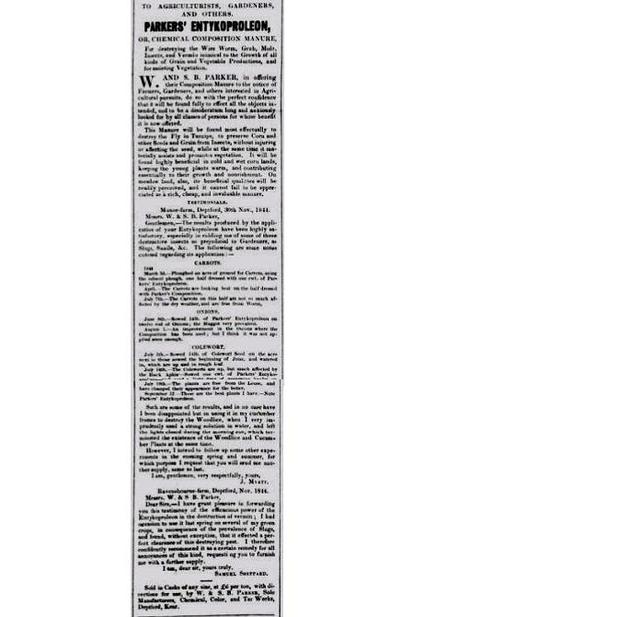

Joseph was obviously willing to help other local people get ahead in business. In 1845 he lent his name to an advertisement for ‘Parkers’ Entykoproleon’. This was a combined fertilizer and pesticide product manufactured by the Messrs Parker, fellow parishioners at St Paul’s. In a glowing testimonial, Joseph provided a diary describing improvements to his carrot, onion and colewort crops after applying the product. A second testimonial is provided by Samuel Sheppard.

LATER YEARS

At the age of 79, Joseph still described himself as a ‘market gardener’, and not ‘retired’ in the 1851 census, however, approaching the age of eighty, he gradually withdrew from running his family business.

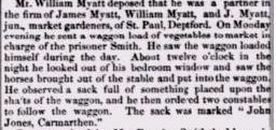

The following excerpt from an article in the Kent Mercury in October, 1852 is part of a description of a court case about some oats stolen from Manor Farm. It shows that Joseph’s sons now had their own business partnership. The family firm ‘Joseph Myatt and Sons’ had ceased and a new company in the names of the three brothers had been formed. It is interesting to note that James was included in the business when he was on Myatt’s Ground at Camberwell. Family relationships must have been good for the three brothers to conduct business together across the two properties.

At the age of 79, Joseph still described himself as a ‘market gardener’, and not ‘retired’ in the 1851 census, however, approaching the age of eighty, he gradually withdrew from running his family business.

The following excerpt from an article in the Kent Mercury in October, 1852 is part of a description of a court case about some oats stolen from Manor Farm. It shows that Joseph’s sons now had their own business partnership. The family firm ‘Joseph Myatt and Sons’ had ceased and a new company in the names of the three brothers had been formed. It is interesting to note that James was included in the business when he was on Myatt’s Ground at Camberwell. Family relationships must have been good for the three brothers to conduct business together across the two properties.

Joseph’s signature on the marriage certificate of one of his grandsons in 1853 is as firm as ever. He continued working into his old age, but always had William and Joseph with him at Manor Farm, as well as grandsons and employees. A new variety of strawberry ‘Admiral Dundas’ was released as late as 1854 so presumably William was responsible its development. Other later Myatt strawberries included ‘Filbert Pine’, ‘Eleanor’, ‘Globe’, ‘Mammoth’, ‘Hautbois’, ‘Myatt’s Surprise’, ‘Crimson Queen’, ‘Cinquefolia’ and ‘Emily’. These may have been grown by Joseph, or perhaps some were developed by James, William or Joseph Jr and the distinction between the Myatts lost over time.

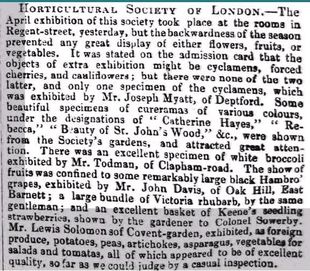

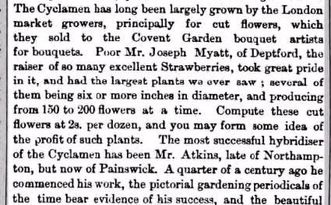

In his later years Joseph exhibited flowers at horticultural shows. One can imagine him in his seventies and eighties leaving the strenuous and consuming occupation of the mass production of fruit and vegetables to his sons and staff while he pottered with his prize-winning cyclamens in the greenhouse. The next item describing a display of his cyclamens appeared in the Morning Post in 1853. Interestingly the same article describes strawberries and Victoria rhubarb displayed by other growers. Thirteen years after his death Joseph Myatt’s cyclamens were still remarked upon, as seen in the following article from the Nottinghamshire Guardian in 1868:

In his later years Joseph exhibited flowers at horticultural shows. One can imagine him in his seventies and eighties leaving the strenuous and consuming occupation of the mass production of fruit and vegetables to his sons and staff while he pottered with his prize-winning cyclamens in the greenhouse. The next item describing a display of his cyclamens appeared in the Morning Post in 1853. Interestingly the same article describes strawberries and Victoria rhubarb displayed by other growers. Thirteen years after his death Joseph Myatt’s cyclamens were still remarked upon, as seen in the following article from the Nottinghamshire Guardian in 1868:

The elderly Joseph Myatt was surrounded by family; as well as his sons William and Joseph Jr and grandchildren who lived and worked at Manor Farm, Eliza and Henry Sheppard had their market garden around the corner in Evelyn Street, and James Myatt and his large family were a few miles away at Myatt Grounds in Camberwell. By now, some of Joseph's grandsons had their own market gardens, including George Myatt in Deptford.

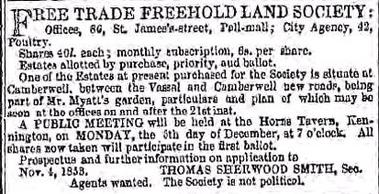

However, change was coming. London was expanding rapidly; railway and housing companies were buying farmland around the city and residential areas grew exponentially. Land around Myatt’s Ground at Camberwell and Manor Farm at Deptford was bought by the Chatham and Dover Railway Company and Housing Development companies. Being tenants, market gardeners had little choice but to reduce their operations or move out. The following advertisement from The London Daily News in 1853 shows that "part of Mr Myatt’s garden" at Camberwell had been sold off for a housing estate.

However, change was coming. London was expanding rapidly; railway and housing companies were buying farmland around the city and residential areas grew exponentially. Land around Myatt’s Ground at Camberwell and Manor Farm at Deptford was bought by the Chatham and Dover Railway Company and Housing Development companies. Being tenants, market gardeners had little choice but to reduce their operations or move out. The following advertisement from The London Daily News in 1853 shows that "part of Mr Myatt’s garden" at Camberwell had been sold off for a housing estate.

A major change for the Myatt family occurred in 1852 when James Myatt moved to Worcestershire, taking the lease of Norval Farm in the village of Offenham near Evesham. James took most of his family with him, but two sons stayed on at a reduced Myatt’s Ground for a few more years with their sister Elizabeth keeping house. With James now out of London and Joseph retired, Manor Farm at Deptford briefly became a business partnership between William Myatt and Joseph Myatt Jr.

JOSEPH MYATT'S DEATH

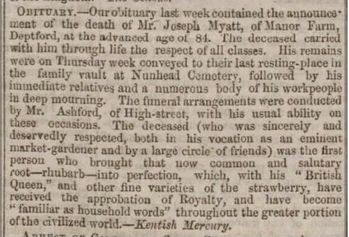

Joseph Myatt died at Manor Farm on 18th January 1855 aged eighty-four. The death notice was printed in the Morning Chronicle on Saturday, 27th January and an obituary appeared in the Kentish Mercury on the same day. This obituary was reprinted in the Staffordshire newspapers. Joseph must have maintained connections with his home county, perhaps staying in contact with his brothers and sisters and their families. The obituary does not mention Staffordshire as his birthplace, so it is hard to know whether his fame in gardening circles had reached the general population there.

JOSEPH MYATT'S DEATH

Joseph Myatt died at Manor Farm on 18th January 1855 aged eighty-four. The death notice was printed in the Morning Chronicle on Saturday, 27th January and an obituary appeared in the Kentish Mercury on the same day. This obituary was reprinted in the Staffordshire newspapers. Joseph must have maintained connections with his home county, perhaps staying in contact with his brothers and sisters and their families. The obituary does not mention Staffordshire as his birthplace, so it is hard to know whether his fame in gardening circles had reached the general population there.

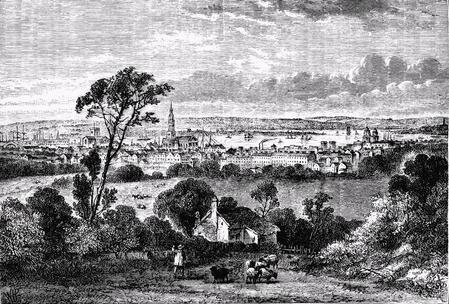

Joseph Myatt is buried in the family vault at Nunhead Cemetery. It is in the highest part of the cemetery which in those days would have had a sweeping view of the great market gardens of south-east London, St Paul’s Church and the river beyond. Nine family members are buried with Joseph in the Myatt vault. Beside it is the Sheppard family vault where Eliza is buried. This nineteenth century view of Deptford was drawn near to where Nunhead Cemetery is located. The tall church in the distance is St Paul’s where Joseph became a senior parishioner. The photograph shows the Myatt vault at Nunhead, being the plainer vault on the left. On the right is another vault with a cross and to the right of that is the Sheppard vault, not seen in this view. (Photo courtesy of Friends of Nunhead Cemetery.)

JOSEPH MYATT'S LEGACY

Joseph Myatt and his sons are honoured at Camberwell by the names of Myatt’s Fields Park and Myatt Road and at Deptford by Myatt Garden Primary School and Manor Avenue. There is also a Myatt Road where James lived in Offenham. The following descriptions of Manor Farm and the surrounding area are taken from 1884 and 1890 histories of Deptford:

James and William Myatt and Eliza Sheppard each named one of their sons Joseph. There were twenty-eight grandchildren in total. The majority of Joseph's grandsons followed their grandfather into market gardening and several granddaughters married farmers and gardeners. Many of their descendants still work in agriculture today.

Joseph Myatt will always be remembered as a pioneer of strawberry cultivation, developing over a dozen new varieties. His work with strawberries was described by Charles Darwin in The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, published in 1868. Myatt strawberries feature in non-fiction too; they are mentioned in at least three Victorian novels, as seen in the following excerpt from Woman of the World, by Catherine Gore:

Joseph Myatt will always be remembered as a pioneer of strawberry cultivation, developing over a dozen new varieties. His work with strawberries was described by Charles Darwin in The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, published in 1868. Myatt strawberries feature in non-fiction too; they are mentioned in at least three Victorian novels, as seen in the following excerpt from Woman of the World, by Catherine Gore:

Joseph Myatt is also remembered fondly as the ‘godfather’ of English rhubarb. No description of the history of rhubarb is complete without mention of his contribution to the establishment of rhubarb in the English diet. Most of the rhubarb and strawberry varieties and other vegetables that Joseph Myatt developed are no longer grown, but Victoria rhubarb is still produced commercially and favoured by many modern home gardeners.